- Managing your Practice

-

- Your Benefits

-

Introducing the ultimate Club MD experience

From work to play, and everything in between, we provide you with access to hundreds of deals from recognizable, best-in-class brands, elevating every facet of your life – from practice supports to entertainment, restaurants, electronics, travel, health and wellness, and more. Your Club MD membership ensures that these deals are exclusive to you, eliminating the need to search or negotiate.

Welcome to the ultimate Club MD experience. Your membership, your choices, your journey.

-

- Advocacy & Policy

-

- Collaboration

- News & Events

-

Stay Informed

Stay up to date with important information that impacts the profession and your practice. Doctors of BC provides a range of newsletters that target areas of interest to you.

Subscribe to the President's Letter

Subscribe to Newsletters

-

- About Us

-

Cultural connections: Collaborating for healing in health care

January 11, 2021

News

In early 2020, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation community members led a group of Tofino health care professionals through a cultural ceremony where they experienced traditional healing practices first-hand. Together, they wanted to explore how these practices and stronger cultural connections might blend with medical care to support people who experience trauma and pain.

First Nations Healer Nora Martin and Cultural Worker Chris Seitcher led the ceremony, which included Tla-o-qui-aht members, physicians, nurses, X-ray and laboratory technicians, and a firefighter.

Martin explains that traditional cleansing ceremonies have been used by her ancestors for generations and continue today. “We carry trauma around with us, and sometimes never deal with it,” she explains. “In our community, if there is a serious incident or death, we do these kinds of ceremonies for community members right away. It makes a big difference.”

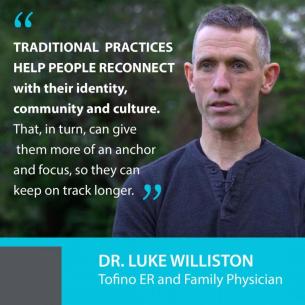

Those benefits caught the attention of Tofino primary care and emergency room physician Dr. Luke Williston. He had seen for himself how traditional cultural practices helped a group of patients who were struggling to deal with trauma and experiencing substance use that required frequent treatment in hospital.

“A First Nations Cultural Worker came to the hospital to do a cleansing ceremony for some patients,” he says. “We didn’t see any of those patients for more than a year after. When I would see them in the community, I could see they were doing better. That is hard to ignore."

“A First Nations Cultural Worker came to the hospital to do a cleansing ceremony for some patients,” he says. “We didn’t see any of those patients for more than a year after. When I would see them in the community, I could see they were doing better. That is hard to ignore."

“While our current medical therapies are good, they do not always hit true with everyone.”

He observes that traditional practices help people reconnect with their identity, community and culture. “That, in turn, can give them more of an anchor and focus, so they can keep on track longer.”

Vision for a healing community

Williston wanted to learn more. With funding from Facility Engagement and the Rural and Remote Division of Family Practice, he connected with Martin and Seitcher to explore how they could work together to introduce health care colleagues to traditional practices, and over time, create a more connected healing community.

Chris Seitcher has worked in the helping field for many years, including as a care aid with Island Health, and for elders in the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation. He runs a weekly men’s group, which he describes as being a supportive, safe space for community members to share stories, history, traumas, and emotions. Traditional chanting and singing are also incorporated to help change the energy.

“This is how we deal with our trauma, our suffering, our pain,” he explains. “When we have safe space and support where we can share things that are happening inside—things we don’t usually talk about—then things start to slowly change.”

Williston feels that health care workers can also benefit from some of these approaches. “We get exposed to a lot of trauma at the hospital all day,” he says. “We all need to find healing for ourselves.”

Exploring the opportunity together

A collaborative plan unfolded. Martin and Seitcher arranged to hold a traditional cultural ceremony that was recorded on video. It incorporated a talking circle, breathing exercises, and drumming and singing led by Hayden Seitcher, also of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation.

Pools were set up at Načiks (Clayoquot Heritage Museum at Monks Point in Tofino) for the group to experience cold water cleansing.

“Any time there was trauma in the community, or family, grief, or loss, we would bring members to the river or ocean to do a cleansing,” explains Martin. “Cold water rebalances us: it refocuses negative energy…to help clear the mind.”

The ceremony was an insightful learning experience for the guests. “It is quite different from our usual kind of medical work—a much slower pace,” says participant Dr. Pam Frazee. “A different part of your brain is working—your emotions are more present.”

Strengthening cultural connections

Over time, the aim of those involved is to introduce traditional healing practices more widely with health care professionals, ambulance crews, firefighters, the coast guard, and police officers—all of whom are exposed to emotional and physical trauma—and to create stronger cultural connections among patients, health care, and emergency professionals.

“These providers work in First Nations communities and may not have that connection yet,” says Williston, who sees benefits of making traditional, non-medical interventions more available to health professionals. He suggests that paramedics, for example, could introduce some of the techniques that help reduce a patient’s anxiety before getting to the hospital.

Additionally, cultural workers could be integrated into the hospital to perform ceremonies for sick patients and those who are soon to be discharged. “That surrounding care might help [patients] stay better, longer,” says Williston.

Seitcher also sees many benefits to blending in traditional practices. “Culture is always around us,” he says. “Culture means connection. We can bring our culture to the hospital and create a safe space to connect and work through some tough issues.”

Martin, reflecting on her first time working with the medical community, says she is pleased to see the openness to new ways and new learning.

It supports an aim of the First Nations Health Authority and BC’s health care system to have First Nations communities and members work in partnership with doctors and health care professionals to support people’s health, wellness and care.

“We have a lot to offer,” she says. “We can help each other out – instead of living and working in isolation – and provide more services to many more people.”

This project was supported by Facility Engagement, a Specialist Services Committee (SSC) Initiative, and the Rural and Remote Division of Family Practice, an Initiative of the General Practice Services Committee (GPSC). The SSC and GPSC are Joint Collaborative Committees of the Government of BC and Doctors of BC